Eli Whitney Muskets Good Guys 2001 Movie Play Again

| Eli Whitney | |

|---|---|

Whitney in 1822 | |

| Born | December 8, 1765 (1765-12-08) Westborough, Province of Massachusetts Bay, British America |

| Died | Jan 8, 1825 (1825-01-09) (aged 59) New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Pedagogy | Yale Higher |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Children | 4 |

| Parent(s) | Eli Whitney, Elizabeth Fay |

| Engineering career | |

| Projects | Interchangeable parts, cotton gin |

| Signature | |

| |

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765 – January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin, ane of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.[1]

Although Whitney himself believed that his invention would reduce the demand for enslaved labor and help hasten the terminate of southern slavery, Whitney'southward invention made upland curt cotton fiber into a profitable ingather, which strengthened the economic foundation of slavery in the United States and prolonged the establishment.[two] Despite the social and economic impact of his invention, Whitney lost many profits in legal battles over patent infringement for the cotton gin. Thereafter, he turned his attending into securing contracts with the government in the manufacture of muskets for the newly formed United states of america Army. He continued making arms and inventing until his death in 1825.

Early life and didactics

Coat of Arms of Eli Whitney

Whitney was born in Westborough, Massachusetts, on December 8, 1765, the eldest child of Eli Whitney Sr., a prosperous farmer, and his wife Elizabeth Fay, also of Westborough.

The younger Eli was famous during his lifetime and after his death by the name "Eli Whitney", though he was technically Eli Whitney Jr. His son, born in 1820, also named Eli, was known during his lifetime and later by the name "Eli Whitney, Jr."

Whitney's mother, Elizabeth Fay, died in 1777, when he was eleven.[iii] At historic period xiv he operated a profitable smash manufacturing performance in his father's workshop during the Revolutionary War.[iv]

Because his stepmother opposed his wish to nourish college, Whitney worked as a subcontract laborer and school teacher to save coin. He prepared for Yale at Leicester University (at present Becker College) and under the tutelage of Rev. Elizur Goodrich of Durham, Connecticut, he entered in the autumn of 1789 and graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1792.[1] [5] Whitney expected to study law merely, finding himself short of funds, accustomed an offer to go to South Carolina as a private tutor.

Petition by Whitney to the selectmen of Westborough, Massachusetts, to run a public schoolhouse, with sample of his penmanship

Instead of reaching his destination, he was convinced to visit Georgia.[4] In the closing years of the 18th century, Georgia was a magnet for New Englanders seeking their fortunes (its Revolutionary-era governor had been Lyman Hall, a migrant from Connecticut). When he initially sailed for South Carolina, among his shipmates were the widow (Catherine Littlefield Greene) and family of the Revolutionary hero Gen. Nathanael Greene of Rhode Isle. Mrs. Greene invited Whitney to visit her Georgia plantation, Mulberry Grove. Her plantation managing director and husbandhoped-for was Phineas Miller, some other Connecticut migrant and Yale graduate (class of 1785), who would get Whitney's business partner.

Career

Whitney is most famous for two innovations which came to accept significant impacts on the United States in the mid-19th century: the cotton fiber gin (1793) and his advocacy of interchangeable parts. In the South, the cotton gin revolutionized the way cotton was harvested and reinvigorated slavery. Conversely, in the N the adoption of interchangeable parts revolutionized the manufacturing industry, contributing profoundly to the U.Due south. victory in the Civil War.[6]

Cotton gin

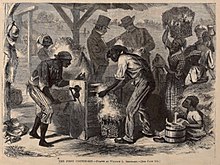

"Get-go cotton gin" from Harpers Weekly. 1869 illustration depicting event of some seventy years earlier.

Cotton fiber Gin Patent. It shows sawtooth gin blades, which were not part of Whitney'south original patent.

The cotton fiber gin is a mechanical device that removes the seeds from cotton, a process that had previously been extremely labor-intensive. The word gin is short for engine. While staying at Mulberry Grove, Whitney constructed several ingenious household devices which led Mrs Greene to innovate him to some businessmen who were discussing the desirability of a machine to separate the short staple upland cotton wool from its seeds, work that was then done by paw at the rate of a pound of lint a day. In a few weeks Whitney produced a model.[seven] The cotton gin was a wooden drum stuck with hooks that pulled the cotton fibers through a mesh. The cotton seeds would not fit through the mesh and fell exterior. Whitney occasionally told a story wherein he was pondering an improved method of seeding the cotton when he was inspired by observing a cat attempting to pull a chicken through a fence, and able to only pull through some of the feathers.[eight]

A unmarried cotton gin could generate up to 55 pounds (25 kg) of cleaned cotton daily. This contributed to the economic development of the Southern United states of america, a prime cotton growing expanse; some historians believe that this invention allowed for the African slavery system in the Southern United States to become more sustainable at a critical point in its evolution.[nine]

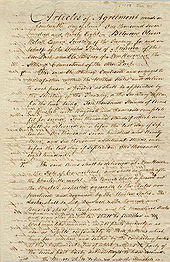

Whitney applied for the patent for his cotton wool gin on October 28, 1793, and received the patent (later numbered as X72) on March 14, 1794,[10] but information technology was non validated until 1807. Whitney and his partner, Miller, did not intend to sell the gins. Rather, like the proprietors of grist and sawmills, they expected to charge farmers for cleaning their cotton – two-fifths of the value, paid in cotton. Resentment at this scheme, the mechanical simplicity of the device and the primitive land of patent law, made infringement inevitable. Whitney and Miller could not build enough gins to run into demand, so gins from other makers found set sale. Ultimately, patent infringement lawsuits consumed the profits (one patent, later annulled, was granted in 1796 to Hogden Holmes for a gin which substituted round saws for the spikes)[7] and their cotton gin company went out of business in 1797.[4] 1 oft-overlooked point is that there were drawbacks to Whitney's first blueprint. There is significant show that the design flaws were solved by his sponsor, Mrs. Greene, just Whitney gave her no public credit or recognition.[11]

After validation of the patent, the legislature of South Carolina voted $50,000 for the rights for that country, while North Carolina levied a license revenue enhancement for five years, from which about $30,000 was realized. There is a claim that Tennessee paid, perhaps, $10,000.[seven] While the cotton gin did non earn Whitney the fortune he had hoped for, it did give him fame. It has been argued by some historians that Whitney's cotton gin was an important if unintended cause of the American Civil War. Later on Whitney's invention, the plantation slavery industry was rejuvenated, eventually culminating in the Civil War.[12]

The cotton wool gin transformed Southern agriculture and the national economic system.[13] Southern cotton wool found ready markets in Europe and in the burgeoning fabric mills of New England. Cotton exports from the U.S. boomed after the cotton gin's appearance – from less than 500,000 pounds (230,000 kg) in 1793 to 93 million pounds (42,000,000 kg) by 1810.[14] Cotton was a staple that could be stored for long periods and shipped long distances, different most agricultural products. It became the U.South.'s chief consign, representing over half the value of U.South. exports from 1820 to 1860.

Whitney believed that his cotton gin would reduce the need for enslaved labor and would aid hasten the finish of southern slavery.[2] Paradoxically, the cotton gin, a labor-saving device, helped preserve and prolong slavery in the United states for another 70 years. Earlier the 1790s, slave labor was primarily employed in growing rice, tobacco, and indigo, none of which were peculiarly assisting anymore. Neither was cotton fiber, due to the difficulty of seed removal. But with the invention of the gin, growing cotton with slave labor became highly profitable – the principal source of wealth in the American Due south, and the basis of borderland settlement from Georgia to Texas. "Rex Cotton" became a dominant economic strength, and slavery was sustained as a key institution of Southern lodge.

Interchangeable parts

Eli Whitney has ofttimes been incorrectly credited with inventing the idea of interchangeable parts, which he championed for years every bit a maker of muskets; all the same, the idea predated Whitney, and Whitney's office in it was 1 of promotion and popularizing, not invention.[xv] Successful implementation of the thought eluded Whitney until near the end of his life, occurring start in others' armories.

Attempts at interchangeability of parts can be traced back every bit far as the Punic Wars through both archaeological remains of boats at present in Museo Archeologico Baglio Anselmi and contemporary written accounts.[ commendation needed ] In mod times the idea developed over decades among many people. An early on leader was Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval, an 18th-century French artillerist who created a fair corporeality of standardization of artillery pieces, although not true interchangeability of parts. He inspired others, including Honoré Blanc and Louis de Tousard, to piece of work further on the idea, and on shoulder weapons equally well as artillery. In the 19th century these efforts produced the "arsenal organization," or American system of manufacturing. Certain other New Englanders, including Helm John H. Hall and Simeon North, arrived at successful interchangeability before Whitney'southward armory did. The Whitney armory finally succeeded non long after his expiry in 1825.

The motives behind Whitney's acceptance of a contract to manufacture muskets in 1798 were mostly monetary. By the belatedly 1790s, Whitney was on the verge of bankruptcy and the cotton gin litigation had left him securely in debt. His New Haven cotton wool gin mill had burned to the footing, and litigation sapped his remaining resource. The French Revolution had ignited new conflicts between Great Britain, France, and the United States. The new American government, realizing the demand to set up for state of war, began to rearm. The War Section issued contracts for the manufacture of 10,000 muskets. Whitney, who had never made a gun in his life, obtained a contract in January 1798 to deliver 10,000 to fifteen,000 muskets in 1800. He had not mentioned interchangeable parts at that time. Ten months afterwards, the Treasury Secretarial assistant, Oliver Wolcott, Jr., sent him a "foreign pamphlet on artillery manufacturing techniques," perchance one of Honoré Blanc'due south reports, after which Whitney starting time began to talk almost interchangeability.

Whitney's gun factory in 1827

In May 1798, Congress voted for legislation that would utilize 8 hundred thousand dollars in order to pay for small arms and cannons in case war with France erupted. It offered a v,000 dollar incentive with an additional 5,000 dollars once that money was wearied for the person that was able to accurately produce arms for the government. Because the cotton fiber gin had not brought Whitney the rewards he believed it promised, he accustomed the offer. Although the contract was for one year, Whitney did not deliver the arms until 1809, using multiple excuses for the delay. Recently, historians have found that during 1801–1806, Whitney took the coin and headed into South Carolina in order to turn a profit from the cotton gin.[16]

Although Whitney's demonstration of 1801 appeared to show the feasibility of creating interchangeable parts, Merritt Roe Smith concludes that it was "staged" and "duped government authorities" into believing that he had been successful. The charade gained him time and resource toward achieving that goal.[xvi]

When the government complained that Whitney'south toll per musket compared unfavorably with those produced in government armories, he was able to calculate an actual price per musket by including fixed costs such as insurance and machinery, which the government had not accounted for. He thus made early contributions to both the concepts of cost accounting, and economic efficiency in manufacturing.

Milling machine

Auto tool historian Joseph W. Roe credited Whitney with inventing the kickoff milling auto circa 1818. Subsequent work by other historians (Woodbury; Smith; Muir; Battison [cited by Baida[16]]) suggests that Whitney was among a group of contemporaries all developing milling machines at virtually the same fourth dimension (1814 to 1818), and that the others were more important to the innovation than Whitney was. (The car that excited Roe may not accept been built until 1825, after Whitney'due south expiry.) Therefore, no one person tin can properly be described as the inventor of the milling machine.

Later life and legacy

Despite his apprehensive origins, Whitney was keenly aware of the value of social and political connections. In building his arms business, he took full advantage of the access that his status as a Yale alumnus gave him to other well-placed graduates, such as Oliver Wolcott, Jr., Secretary of the Treasury (class of 1778), and James Hillhouse, a New Haven developer and politico.

His 1817 marriage to Henrietta Edwards, granddaughter of the famed evangelist Jonathan Edwards, girl of Pierpont Edwards, head of the Democratic Party in Connecticut, and starting time cousin of Yale'southward president, Timothy Dwight, the state'due south leading Federalist, farther tied him to Connecticut's ruling elite. In a concern dependent on authorities contracts, such connections were essential to success.

Whitney died of prostate cancer on January 8, 1825, in New Haven, Connecticut, just a calendar month after his 59th altogether. He left a widow and his four children behind. One of his offspring, Eli Whitney Iii (known as Eli Whitney Jr.), was instrumental in building New Haven, Connecticut's waterworks.[ commendation needed ] During the course of his affliction, he reportedly invented and constructed several devices to mechanically ease his pain.

The Eli Whitney Students Program, Yale Academy'south admissions program for non-traditional students, is named in honor of Whitney, who not only began his studies there when he was 23,[17] but also went on to graduate Phi Beta Kappa in just iii years.

Come across also

- Whitney family

- Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Eli Whitney Museum

References

- ^ a b "Elms and Magnolias: The 18th century". Manuscripts and Athenaeum, Yale University Library. August 16, 1996. Retrieved March nineteen, 2008.

- ^ a b "Eli Whitney Patents the Automobile He Idea Would Help Terminate Slavery". Today In History. Office of the State Historian. March 14, 2020. Retrieved Jan 18, 2022.

- ^ "Westborough Deaths". Massachusetts Vital Records to 1850. New England Celebrated Genealogical Society. 2001–2008. p. 275. Archived from the original on April 15, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c MIT Inventor of the Week archive profile. From a website funded and administered past Lemelson-MIT Program. Accessed March 18, 2008.

- ^ Who Belongs To Phi Beta Kappa Archived January 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Phi Beta Kappa website, accessed October 4, 2009

- ^ New Georgia Encyclopedia: Eli Whitney in Georgia Archived April 5, 2013, at the Wayback Auto. Accessed March nineteen, 2008.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Gettysburg Compiler - Google News Archive Search (Apr 27, 1918). "Cat Gave Him Thought". news.google.com . Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ "Eli Whitney'southward Patent for the Cotton Gin". Usa National Archives. August 15, 2016. Retrieved April xiii, 2021.

- ^ "Patent for Cotton Gin". History Reference Eye . Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ Eli Whitney Project A website for The Eli Whitney Project

- ^ "Top Five Causes of the Ceremonious War". Americanhistory.about.com. January 26, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ The Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop A website for The Eli Whitney Museum in Hamden, CT.

- ^ "Monthly Summary of Commerce and Finance of the Usa, Issues 1-three". Monthly Summary of Commerce and Finance. U.S. Department of the Treasury. 1895–1896: 290.

- ^ Byson, Bill (2011). At Home: A Short History of Private Life . Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 412. ISBN9780767919395.

- ^ a b c Baida, Peter (May–June 1987). "Eli Whitney'due south Other Talent". American Heritage. 38 (4). Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ^ "Eli Whitney Students Program – A Programme for Non-Traditional Students". yale.edu. New Oasis, CT: Yale Academy. Retrieved Nov 21, 2011.

Further reading

- Battison, Edwin. (1960). "Eli Whitney and the Milling Auto." Smithsonian Journal of History I.

- Cooper, Carolyn, & Lindsay, Merrill Yard. (1980). Eli Whitney and the Whitney Armory.

- Whitneyville, CT: Eli Whitney Museum.

- Dexter, Franklin B. (1911). "Eli Whitney." Yale Biographies and Annals, 1792–1805. New York, NY: Henry Holt & Company.

- Hall, Karyl Lee Kibler, & Cooper, Carolyn. (1984). Windows on the Works: Industry on the Eli Whitney Site, 1798–1979.

- Hamden, CT: Eli Whitney Museum

- Hounshell, David A. (1984), From the American System to Mass Production, 1800–1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United states, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins Academy Press, ISBN978-0-8018-2975-8, LCCN 83016269, OCLC 1104810110

- Lakwete, Angela. (2004). Inventing the Cotton wool Gin: Motorcar and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, Physician: Johns Hopkins University Printing.

- Smith, Merritt Roe. 1973. "John H. Hall, Simeon North, and the Milling Machine: The Nature of Innovation among Antebellum Arms Makers." Technology & Civilization 14.

- Woodbury, Robert Southward. (1960). "The Legend of Eli Whitney and Interchangeable Parts." Technology & Culture 1.

- Iles, George (1912). Leading American Inventors. New York: Henry Holt and Visitor. pp. 75–103.

- McL. Green, Constance – Edited by Oscar Handlin. (1956). Eli Whitney & The Birth of American Engineering science. Library of American Biography serial.

- Roe, Joseph Wickham (1916), English language and American Tool Builders, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, LCCN 16011753 . Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (LCCN 27-24075); and by Lindsay Publications, Inc., Bradley, Illinois (ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7).

External links

- The Eli Whitney Museum

- Eli Whitney Biography on at Whitney Research Group

- Inventor of the Week: Eli Whitney (MIT)

- Entry in New Georgia Encyclopedia Archived Apr 5, 2013, at the Wayback Automobile

- Photograph of house in which the Cotton wool Gin was invented, Wilkes County, Georgia, ca. 1910

-

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource: - "Whitney, Eli". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- "Whitney, Eli". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Whitney, Eli". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 611.

- "Whitney, Eli". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Whitney, Eli". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1889.

- "Whitney, Eli". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Letter of the alphabet from Eli Whitney to his Male parent regarding his invention of the cotton gin, September eleven, 1793

- Alphabetic character from Thomas Jefferson to Eli Whitney, Jr. regarding his cotton gin patent, November 16, 1793

- Obituary for Eli Whitney, in Niles Weekly Register, January 25, 1825

- Eli Whitney papers (MS 554). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale Academy Library. [1]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eli_Whitney

0 Response to "Eli Whitney Muskets Good Guys 2001 Movie Play Again"

Post a Comment